Deep dive in the sea of memory

Commentary: Demand for more flash is good for Apple margins

Like many of my readers, I recently went through the process of purchasing an iPhone 5 as well as an iPad Mini. One of the first things you notice when shopping for one of Apple’s latest devices is the sheer number of choices and decisions there are to be made, and I’m not just talking about black or white. While the iPhone 5s all come with 4G LTE wireless capabilities, there are three different memory capacities available. The iPads and iPad Minis come with choices for both memory and wireless connectivity. Today I want to focus on memory, specifically, NAND Flash memory, so we’re going to hone in on its costs and associated margins in the iPhone 5.

So I’m hovering over the shiny new iPhones in the packed Apple store and trying to make up my mind before the crazed Christmas shoppers behind me buy them all up. How much memory do I need (want)? How much more am I willing to spend in order to get it? Will it really make a difference in terms of how satisfied I am with the device’s performance? Well, I can’t answer that last question for any of you—that depends on whether you’re a serious app and video junkie during the commute each day, or whether you simply use your iPhone 5 to read your wife’s daily HoneyDo text message. But when it comes to memory versus price, I can provide some perspective.

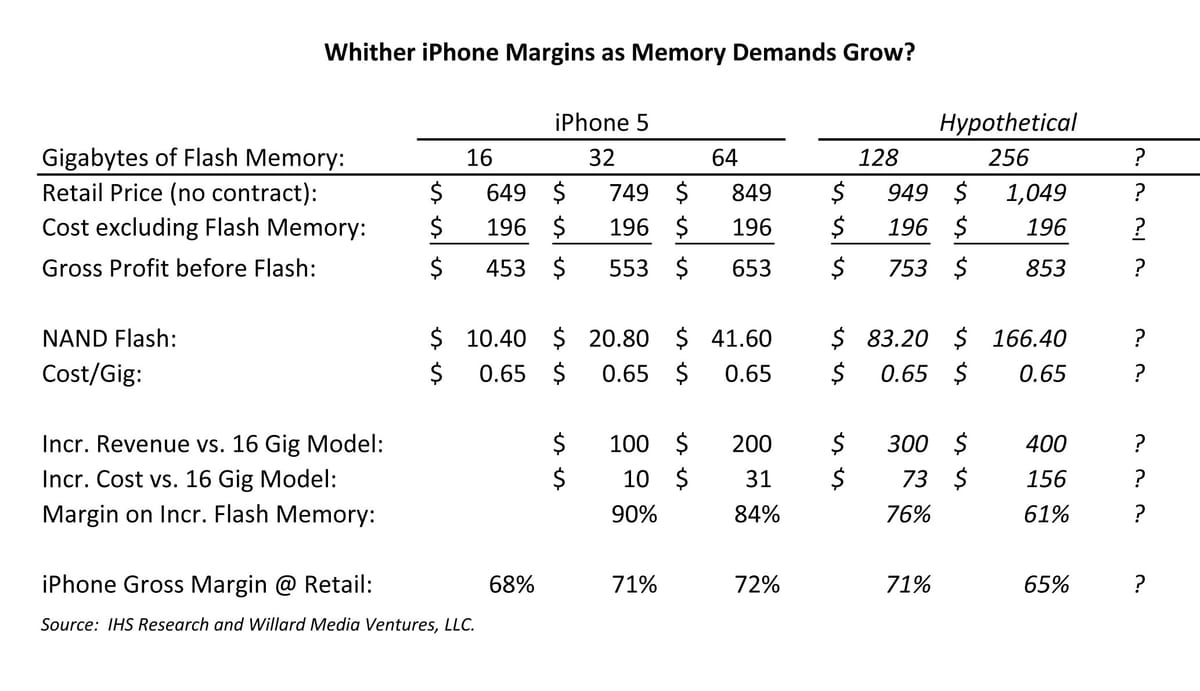

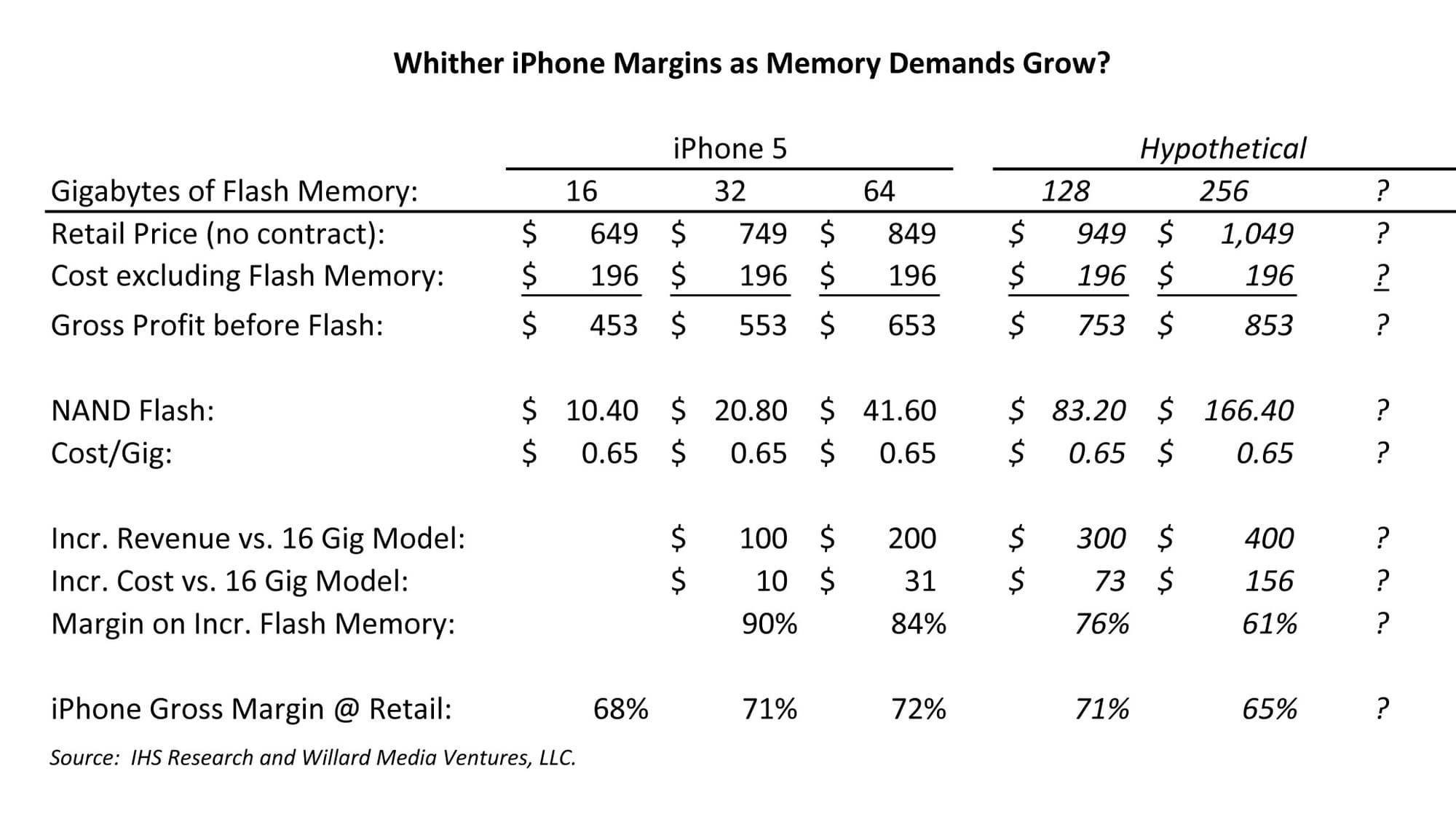

As I compared and contrasted the options in terms of memory and pricing, I couldn’t help but notice that Apple gets $100 more per handset for an extra 16 Gigs of memory over the base 16 Gig model, and it gets $200 more for 64 Gigs of flash memory compared with the base model. That’s a quadrupling of memory (+300% versus the base model). Sounds like a good deal, right? Well as it turns out, it really IS a good deal…for Apple and its gross margins.

Plenty of research firms have reported on their “teardown” of the new iPhone 5. The reports take iPhone 5s apart and identified the component manufacturers (more on that below) and also the costs of all the piece parts.

The consensus is that the base model costs just over $200 for the components and assembly. Included in that price is $10 for the 16 Gigs of flash memory, or about $0.65/Gig. Add another 16 Gigs and you add another $10 more in cost. For the 64 Gig model, the cost for flash is just over $40, or (you guessed it), $0.65/Gig. Everything else in the handset costs the same price.

In other words, Apple earns an incremental margin of about 90% when you upgrade from the 16 Gig model to the 32 bit model—it collects $100 more but it spends only $10 more. The 64 Gig model provides Tim Cook and the gang with an 84% incremental margin versus the base model ($200 more in revenue, $31 more in cost). That’s a sweet deal and it means that the already impressive 68% gross margin on the 16 Gig model increases to 72% with the 64 Gig model (based on retail prices).

What, in turn, might that mean as consumers demand ever more memory? We ran a few hypothetical numbers. Given the doubling in Gigabytes for each “better” model, and the fact that the memory comes at a fixed cost per Gig (based on IHS’ research), there would be a diminishing return beyond the 64 Gig level—today.

So if Apple had come out with a 128 Gig or even a 256 Gig version of the iPhone 5, but stuck to its $100 per iteration price increase, its overall margin would start to fall back because of the (apparently) fixed cost of flash memory per Gig. It wouldn’t have sold too many at a price of $1,049 anyways, but there would have been a few early adopters who needed (wanted) the top-of-the-line model. But that wouldn’t be as good for Apple’s bottom line.

As we evolve to the iPhone 6 or iPhone 10, that flash memory capacity is virtually guaranteed to keep growing. But Apple will balance that growth alongside the declines in the cost of flash memory that should come as technology advances and smart device volume explodes. And it will maintain that balancing act in order to maximize margins.

A note on margins—the number of handsets sold through wireless service providers is vastly larger than the number of devices sold directly at retail. Verizon doesn’t pay $649 for every 16 Gig handset it buys, but handset subsidies (the amount Verizon pays for you when you sign a contract) probably run between $200 and $300 per device. Nevertheless, the incremental margins Apple earns increase between the 16 Gig and the 64 Gig models, whether Verizon is paying $400, $500 or $600 for each of its millions of iPhones. And that’s the point I’m making here today—Apple (and Tim Cook) deserve better than Wall Street’s delivered of late, for managing not only to build the coolest devices out, but also managing costs versus demand to make them among the most profitable.

Finally, on the suppliers. That little ongoing tiff over patents between Samsung and Apple has been well documented, and based on the iPhone 5 teardown, it appears Apple is (not surprisingly) broadening its vendor base. As we’ve long known, Sandisk is supplying memory chips to Apple, and at least some of the batteries that Samsung used to supply are now coming from Sony. The iPhone 5 also contains wireless processors from Qualcomm, Skyworks Solutions, Avago Technologies and Triquint Semiconductor. I’m still pounding the table on Sandisk, especially now that Samsung and Apple are no longer BFF’s.